Negotiation Rhythms #2: Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.

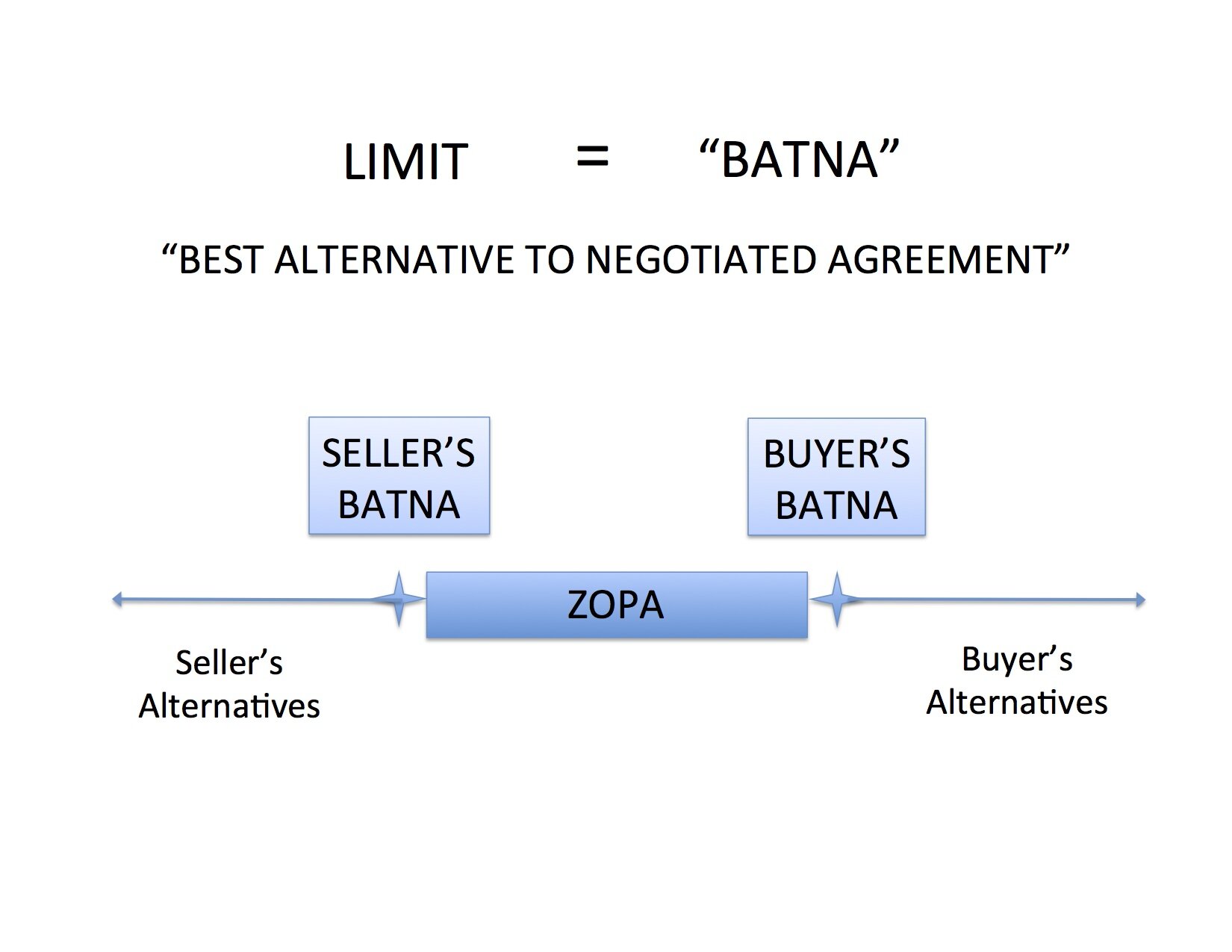

We know we want to push beyond our limits to capture as much value as possible in a negotiation. But how do we define those limits? It takes a five-word phrase to bring this concept into focus: Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement (“BATNA”).

The BATNA for a car buyer might be the same car at a nearby dealership for $20,000. The BATNA for a home seller might be an offer from another party for $1 million. The BATNA for a child trading baseball cards might be to hold onto his favorite cards and enjoy looking at them rather than to trade them away.

Any agreement below (or, for a maximum limit, above) a BATNA would leave the negotiator worse off than in the absence of that particular agreement. Said another way, the negotiator would be better off with some other option – their BATNA – than accepting an agreement on those terms.

To properly identify a BATNA, we must do a lot of calculating, daydreaming, and going out in the world to test alternatives. But this creative process is necessary. When we believe that the only alternative is the one at hand, our negotiation position is dangerously weak. It is also dangerously ineffective because it leads to an arrangement that does not, in fact, make the negotiator better off than without it. And any deal that is not in both parties’ best interests is unstable and likely to collapse after it is made.

Countless factors go into naming and ranking one’s alternatives to arrive at a BATNA, and even then it is impossible to do so clearly as those factors cannot all be outlined in numerical format. A better offer might be less certain of being completed, so it might be more advantageous to make an agreement on less favorable terms today. For example, the other job offer might not be certain even though it appears it would be more advantageous if it were finalized. This is the old saying that a bird in the hand is better than two in the bush, and this can be dangerous for those who optimistically negotiate as if their imaginary alternatives are already in the hand. In the other extreme, this is very limiting for those who are very fearful of uncertainty, as they will accept disadvantageous terms for the simple purpose of having certain terms when a bit of risk in pursuit of a better alternative could have led to greater results.

Timing is important in other ways as well, as a negotiator with more time to come to an agreement will have more chances to find alternatives to the agreement at hand. "Wait and see" becomes a BATNA in itself. The opposite of this would be a party who must have resolution today, which would, of course, limit the alternatives.

Beyond hard limits on time, some people do not enjoy the back and forth process of negotiating. They might prefer to take this deal, and even to accept much less of the middle than is possible to capture, than to continue to seek alternatives or negotiate deals. For these people, the process itself inhibits the growth of BATNAs.

We’ll see in the next post – Negotiation Rhythms #3: Sales & Threats – how brainstorming or eliminating BATNAs changes the ZOPA and improves or weakens our force in negotiation.

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.

Negotiation Rhythms #1: Zone of Possible Agreement

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.

Each party will enter a negotiation with the knowledge of their limits and the desire to make as favorable a deal as possible.

We begin our illustration of the basic negotiation rhythms with the fundamental negotiation question from Harvard Negotiation Project’s classic Getting to Yes[1]: Is there a Zone of Possible Agreement (“ZOPA”) between the limits set by each party?

An agreement is possible if the seller's limit is lower than the buyer's limit. Here's an example:

If an engineer is willing to work for a salary of $100K and a company recruiting that engineer is willing to pay $120K, there would be a ZOPA between $100K and $120K.

However, there would be no ZOPA if the amounts were reversed and the company would not offer more than $100K and the engineer would not accept less than $120K.

Capturing the ZOPA

Presuming that there is a ZOPA, the seller will want to sell for as much over the seller’s minimum as possible, and the buyer will want to buy for as much below the buyer’s maximum as possible.

It would be best for the seller to settle on a price at buyer’s maximum and for buyer to settle on a price at seller’s minimum.

Each is free to try to capture as much of the amount within the ZOPA as possible, especially if they do not know one another’s limits.

Hiding the ZOPA

The danger comes when one or more parties push so hard to settle on an agreement well above their minimum or below their maximum that they fail to discover that there is a ZOPA between the parties.

For example, the engineer would be at an advantage in the first example above if she convinced the company that she would not accept a salary below $120K. By pushing for $120K, she might end up with the maximum possible salary available from the company. However, she would end up with no deal at all – and have missed the chance to make a desirable agreement at somewhere between $100K and $120K – if she convinced the company she would take no less than $125K.

The opposite is also true. If the company convinced the engineer that they could offer no more than $95K, they would have convinced the engineer that there was no ZOPA and killed the deal.

ZOPA Conclusion

Each party has two conflicting goals in a negotiation:

1. Transparency: To discover a possible point of agreement, if one exists. This requires each party to be transparent enough about their limits that the parties can identify whether there is a ZOPA. If the parties kill the deal, they will have sacrificed the value of a beneficial agreement.

2. Ambiguity: To settle on a price that is as close to the other party’s limit as possible. This requires each party to be ambiguous in communicating their limits to encourage the opposing party to believe the ZOPA and their potential gain are smaller than they actually are. If a party settles at their limit, they will have sacrificed the benefit they could have captured by pushing to settle closer to the other party's limit.

Our next post, #2: Best Alternatives to Negotiated Agreement, illustrates how negotiators set their limits. Post #3: Sales & Threats shows the flexibility of the pattern by illustrating how negotiators use sales techniques to change the other party’s limit.

[1] Roger Fisher, William Ury and Bruce Patton, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In.

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.