Negotiation Rhythms #3: Sales & Threats

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.

Mary Russell counsels individual employees and founders to negotiate, maximize and monetize their stock options and other startup stock. She is an attorney and the founder of Stock Option Counsel. You are welcome to contact Stock Option Counsel at info@stockoptioncounsel or (650) 326-3412.

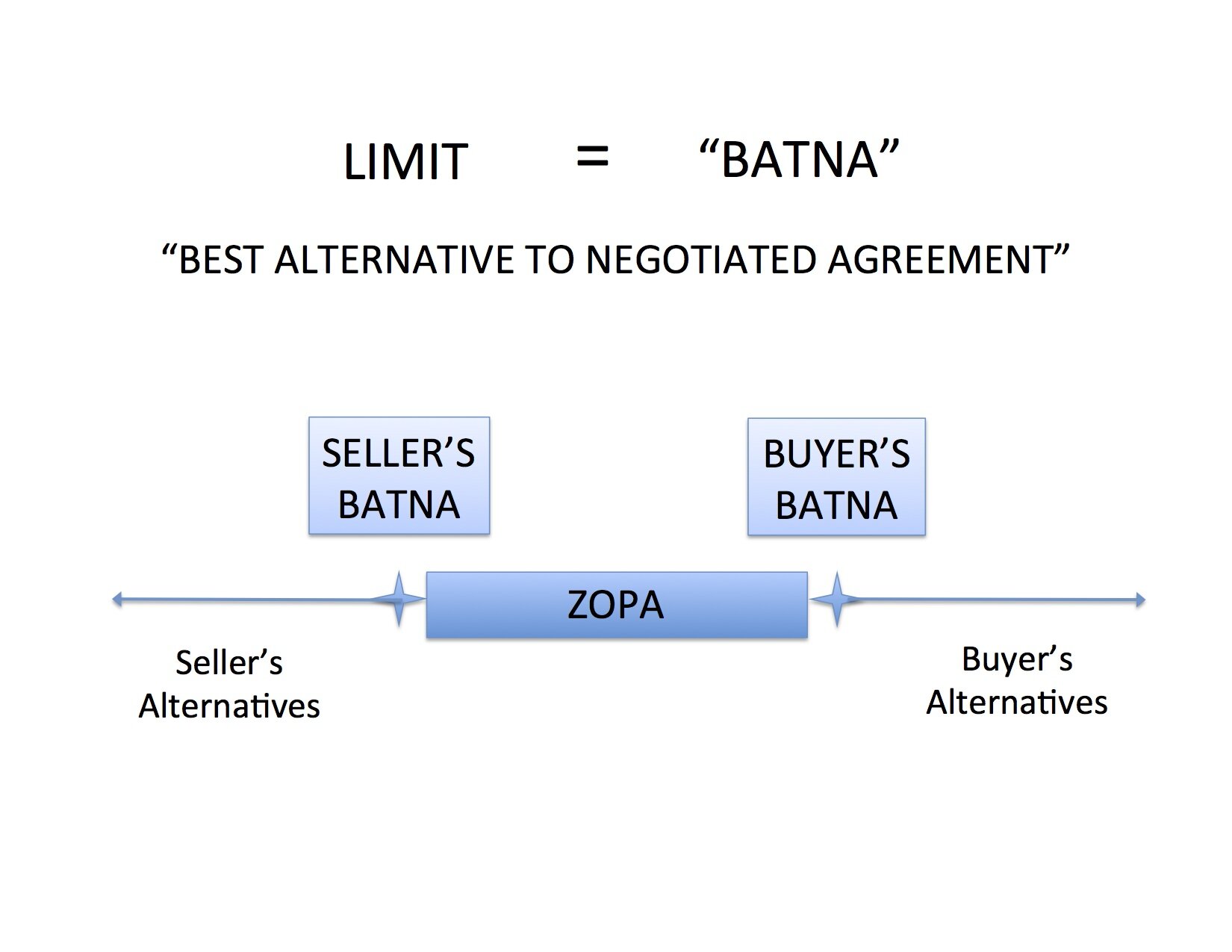

There are two ways to increase or decrease another party’s limit in a negotiation – sales and threats.[1] The picture above takes some of the mystery out of the salesman and the thug -- they're both just working as negotiators to change the perception of the current offer in comparison to the other party's BATNA – Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement.

Selling improves the perception of the quality of the present offer so that the outside alternatives are unattractive by comparison. Threats decrease the attractiveness of outside offers or the possibility of making no deal and sticking with the status quo.

Threats

An ongoing employment lawsuit over no-hire agreements among Silicon Valley companies featuring Steve Jobs provides a strangely relevant example of the power of threats.

Edward Colligan, former CEO of Palm, has said in a statement that Jobs was concerned about Palm’s hiring of Apple employees and that Jobs “proposed an arrangement between Palm and Apple“ [2] to prohibit either party from recruiting the others' employees.

That would have been a simple offer of an agreement (however illegal that arrangement might have been) if Colligan had access to the undisturbed alternative of not participating and keeping the status quo.

But Colligan has said that Jobs’ next negotiation move was to make the alternative of nonparticipation very unappealing with the threat of patent lawsuits that would cost Palm and Apple a great deal of money. Jobs followed this threat with a reminder of just how unpleasant such litigation would be for Palm, considering the fact that Apple had vast resources to endlessly pursue the lawsuits: "I’m sure you realize the asymmetry in the financial resources of our respective companies …."

Even though most of us don’t use threats in a negotiation, it’s part of the logic of negotiation rhythms.

Selling

Selling is the more common (and generally legal) way to address the fact that the other party has choices outside the present negotiation. As we discussed in the prior posts, a party's price or terms limits are defined by his or her best alternative outside of making an agreement in the present negotiation. Selling moves the limit when it can make the present offer more appealing than what had been perceived as an outside alternative.

Many people resist “selling themselves” in a salary negotiation because they are embarrassed to discuss their “value.” The logic of BATNA and negotiations provides some relief from this embarrassment, for it reframes “selling” from bluffing and puffing to describing and distinguishing one’s past experience and intended role in the organization.

Since the employer’s limit is not defined by an individual’s value, but by the employee’s differentiation from the field of candidates, the task of negotiating becomes more fact-based and less fear-driven. This logic encourages progress from the attitude of “Oh, they see who I am and hate me,” toward the sales approach of “Oh, it seems they need more information about what I offer in terms of my past experience and my role going forward.”

As an employee’s offer of services becomes distinguishable from the employer’s alternatives, the employer’s perception of the BATNA will change.

Consider an employer who believes there’s an equal candidate available for $120,000 and is entertaining another’s proposal to perform the role for $140,000. Without “selling” the offer of one’s services, the employer has no information with which to make a distinction between the two alternatives. The process of selling oneself to the employer is not to prove one’s inner worthiness at $140,000, but to show and tell that the employer is choosing between two distinguishable candidates.

(For those still interested in threats, distinguishing one’s skills is a form of a threat when it comes to negotiating with a current employer. Every element of the description one’s current performance and ongoing role is a threat of what the employer would have to work without or try to replace.)

What an employer would have once considered a better alternative – such as another equal offer for $120,000 – loses its appeal in light of the truth (sales pitch) of the $140,000 offer. If they are no longer equal in the mind of the employer, he or she must consciously decide if the other candidate at the lower price is still a better alternative. While there is no guarantee that the employer will prefer to pay more, the process of selling pushes the employer to the choice based on the true distinctions in the qualities of the candidates.

[1] Roger Fisher, William Ury and Bruce Patton, Getting to Yes: Negotiating Agreement Without Giving In. Gerald B. Wetlaufer, The Rhetorics of Negotiation (posted to SSRI).

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.

Negotiation Rhythms #2: Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.

We know we want to push beyond our limits to capture as much value as possible in a negotiation. But how do we define those limits? It takes a five-word phrase to bring this concept into focus: Best Alternative to Negotiated Agreement (“BATNA”).

The BATNA for a car buyer might be the same car at a nearby dealership for $20,000. The BATNA for a home seller might be an offer from another party for $1 million. The BATNA for a child trading baseball cards might be to hold onto his favorite cards and enjoy looking at them rather than to trade them away.

Any agreement below (or, for a maximum limit, above) a BATNA would leave the negotiator worse off than in the absence of that particular agreement. Said another way, the negotiator would be better off with some other option – their BATNA – than accepting an agreement on those terms.

To properly identify a BATNA, we must do a lot of calculating, daydreaming, and going out in the world to test alternatives. But this creative process is necessary. When we believe that the only alternative is the one at hand, our negotiation position is dangerously weak. It is also dangerously ineffective because it leads to an arrangement that does not, in fact, make the negotiator better off than without it. And any deal that is not in both parties’ best interests is unstable and likely to collapse after it is made.

Countless factors go into naming and ranking one’s alternatives to arrive at a BATNA, and even then it is impossible to do so clearly as those factors cannot all be outlined in numerical format. A better offer might be less certain of being completed, so it might be more advantageous to make an agreement on less favorable terms today. For example, the other job offer might not be certain even though it appears it would be more advantageous if it were finalized. This is the old saying that a bird in the hand is better than two in the bush, and this can be dangerous for those who optimistically negotiate as if their imaginary alternatives are already in the hand. In the other extreme, this is very limiting for those who are very fearful of uncertainty, as they will accept disadvantageous terms for the simple purpose of having certain terms when a bit of risk in pursuit of a better alternative could have led to greater results.

Timing is important in other ways as well, as a negotiator with more time to come to an agreement will have more chances to find alternatives to the agreement at hand. "Wait and see" becomes a BATNA in itself. The opposite of this would be a party who must have resolution today, which would, of course, limit the alternatives.

Beyond hard limits on time, some people do not enjoy the back and forth process of negotiating. They might prefer to take this deal, and even to accept much less of the middle than is possible to capture, than to continue to seek alternatives or negotiate deals. For these people, the process itself inhibits the growth of BATNAs.

We’ll see in the next post – Negotiation Rhythms #3: Sales & Threats – how brainstorming or eliminating BATNAs changes the ZOPA and improves or weakens our force in negotiation.

Attorney Mary Russell counsels individuals on startup equity, including:

You are welcome to contact her at (650) 326-3412 or at info@stockoptioncounsel.com.